Due: Thursday, November 20, 2014, 23:59

Goal

The goal of this project is to craft a JIT-spraying exploit.

All work in this project must be done on the VirtualBox virtual machine provided on the course website; see below for information about this environment. Note: This is not the same VM we used for the previous projects!

You are given a single target binary which contains a JavaScript JIT. The program takes a JavaScript file as input and compiles and runs it. Unlike a web browser which would contain numerous external functions accessible via the DOM, target only exposes three external functions: print which prints its arguments to the console, load which takes a single string argument which is a path to a JavaScript file to load and run, and exploit which takes a single integer argument.

The exploit function simulates a vulnerability by jumping to the address specified by the argument.

Your task is to write one or more JavaScript files that will perform a JIT spray and then get a local shell.

Preliminaries

1. Get the sandbox-1.2 virtual machine. sandbox-1.2.ova Again, this is not the same VM we used in the previous projects.

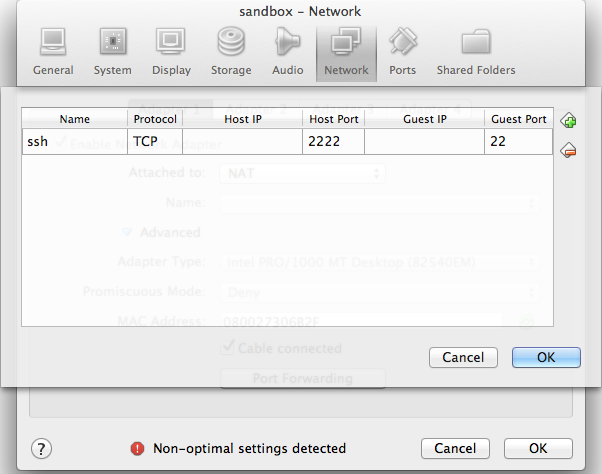

2. Go to Settings > Network > Adapter 1 > Port Forwarding and forward a port from the host machine to port 22 in the guest:

|

Note that if you also used port forwarding on port 2222 for a previous project, SSH will get very upset, because the new VM's key is different and SSH suspects a man-in-the-middle attack. It will tell you what line in .sshknown_hosts is responsible, and you can delete this line and try again.

3. Download and unpack project3.

user@ubuntu:~$ wget http://www.cs.jhu.edu/~s/teaching/cs460/2014-fall/project3.tar.gz user@ubuntu:~$ tar zxf project3.tar.gz

Getting started

The JavaScript JIT that is linked into target is Google's v8 which is used in Google Chrome. The JIT is lazy in the sense that when it sees a new function to compile, it will not actually compile it until the first time it is executed. Thus, it is not sufficient to create a function, you actually need to call it before it will JIT the code.

function spray(x)

{

if (x == 0)

return 0;

var y = x ^

/* JIT spray code */;

return y;

}

spray(0);

The early-exit in spray is to prevent the JITted code from actually being executed in the call to spray(0) which we needed to generate code for spray (i.e., it's a minor optimization).

Starting off the JIT spray code by XORing the variable x also seems to prevent v8 from optimizing the whole expression into a constant.

The first thing you should try doing is including some additional literal values in the spray function and looking at the code that is produced.

For example, try putting into the above code.

var y = x ^ 0x1 ^ 0x2 ^ 0x4 ^ 0x8 ^ 0x10 ^ 0x20 ^ 0x40 ^ 0x55aa;

The target binary comes with an additional feature: it can print out the JITted code by passing the -p command line option. Note: This option is only designed to help you in the creation of your exploit. We will not be testing your code with this option.

If we run ./target -p sploit.js on the above code, we see the sequence of XORs:

0x4bf54a38 88 83f002 xor eax,0x2 0x4bf54a3b 91 83f004 xor eax,0x4 ;; debug: position 65 0x4bf54a3e 94 83f008 xor eax,0x8 ;; debug: position 87 0x4bf54a41 97 83f010 xor eax,0x10 ;; debug: position 109 0x4bf54a44 100 83f020 xor eax,0x20 ;; debug: position 131 0x4bf54a47 103 83f040 xor eax,0x40 ;; debug: position 154 0x4bf54a4a 106 3580000000 xor eax,0x80 ;; debug: position 177 0x4bf54a4f 111 3554ab0000 xor eax,0xab54 ;; debug: position 200

The first column is the address where the code was JITted (but notice that it will change each time you run this so your values are likely different from mine), the second is the offset into the function, the third is the actual bytes that make up the instruction, the fourth is the x86 code produced.

Notice that it has modified the value that is to be XORed! Also notice that it has used two different xor instructions. For small values, it uses the instruction xor r/m32,imm8 which has encoding 83 /6 imm8 (see the Intel manual if you're unsure what that means). For large values, it uses xor eax,imm32 which has encoding 35 imm32. You're going to be using large values so the second is the only one that matters here.

In addition, to the modification the compiler makes to the integers (which has to do with how it internally represents integers), there is one further restriction. If you try to XOR an integer larger than 0x3fffffff, the generated code is not nearly as compact. Fortunately, that will not be an issue if you use cmp al as your chaining instruction as it has opcode 3c.

To assist in the creation of your exploit, we have provided a x86tojit.sh BASH script. It takes as an argument an assembly file (see example.s in the project tarball) and produces the encoding of the instructions it contains:

user@ubuntu:~/project3$ ./x86tojit.sh example.s b1 08 mov cl,0x8 b0 64 mov al,0x64 d3 e0 shl eax,cl b0 63 mov al,0x63 d3 e0 shl eax,cl b0 62 mov al,0x62 d3 e0 shl eax,cl b0 61 mov al,0x61 50 push eax

As a first step, modify this script or write a similar one that will produce the JavaScript code you need rather than constructing it by hand. E.g., my modifications (which amounted to 20 extra lines of sed and bash statements) produce the following for the first few lines.

user@ubuntu:~/project3$ ./x86tojit.sh example.s 0x1e0458c8 ^ // mov cl,0x8 0x1e325848 ^ // mov al,0x64 0x1e7069c8 ^ // shl eax,cl ...

When ./target sploit.js is run, the result should be a local shell:

user@ubuntu:~/project3$ ./target sploit.js $ echo hello hello $ exit

To do that, you're going to need to write some shell code. Take a look at Aleph One's code from the reading. Essentially, you need to arrange for eax to have value 11, ebx to point to the string “/bin/sh”, ecx to point to the argv array and edx to point to the environ array. You can construct the string and the arrays on the stack.

Finally, since where the code is JITted each time is random, you're going to need to JIT a bunch of copies of it (e.g., using load or eval in a loop) and then use exploit to jump there. Try to make your exploit as reliable as possible but it's okay if the target crashes the first few times we try to run it.

Deliverables

You are to provide a tarball (i.e., a .tar.gz file) containing the following files:

README: YourREADMEfile must contain the name of all group members at the top. Below that, describe how yourx86tojit.sh(or similar) script works, how your shell code works, and how your JIT spray works.shellcode.s: Shellcode (in the format ofexample.s) which you will run your modifiedx86tojit.sh(or similar) script on to produce your JavaScript.Your modified

x86tojit.sh(or comparable script) that turns yourshellcode.sinto JavaScript.Your JavaScript files. The main file should be called

sploit.jsand you may have as many additional helper files as you wish.

user@ubuntu:~/project3$ tar zcf p3.tar.gz README shellcode.s x86tojit.sh *.js

We should be able to run your exploits by running:

user@ubuntu:~/project3$ tar zxf p3.tar.gz user@ubuntu:~/project3$ ./target sploit.js

It may take a few attempts to work correctly due to the randomness, but try to make it as robust as you can (see below).

Making the exploit robust

To make the exploit robust, you're going to want to take a few actions to reduce the amount of randomness you have to deal with.

First, you want to make the code you're spraying pretty large and most of that is going to be filled with a JITted NOP sled. For some reason, functions that are too large do not behave the way we want with the series of XORs. So experiment using -p to get a sense of how many NOPs you can insert before you lose the chained XORs.

Notice that the JITted output contains both unoptimized code where each XOR takes 13 bytes of code

0x407546f4 148 90 nop 0x407546f5 149 50 push eax 0x407546f6 150 b89090903c mov eax,0x3c909090 0x407546fb 155 5a pop edx 0x407546fc 156 e81f4cfdff call 0x40729320 ;; debug: position 94

whereas the optimized version consists of a single 5-byte instruction

0x4076e282 98 359090903c xor eax,0x3c909090 ;; debug: position 94

What this means is that even discounting the fixed beginnings and endings of your JITted functions, 72% of your JITted code is not usable. Worse still, even if you jump into the middle of the optimized code, there's still a chance you'll land on an XOR rather than in one of the NOP bytes. But that's not all, the JIT also produces a lot of extra data that isn't executable.

Linux exposes information about a process's address space using the /proc file system. A process can get information about its own address space by reading /proc/self/maps. As an example, here's what the cat process's address space looks like.

user@sandbox:~$ cat /proc/self/maps 08048000-08053000 r-xp 00000000 fc:00 28 /bin/cat 08053000-08054000 r--p 0000a000 fc:00 28 /bin/cat 08054000-08055000 rw-p 0000b000 fc:00 28 /bin/cat 09d64000-09d85000 rw-p 00000000 00:00 0 [heap] b73c1000-b75c1000 r--p 00000000 fc:00 10731 /usr/lib/locale/locale-archive b75c1000-b75c2000 rw-p 00000000 00:00 0 b75c2000-b776b000 r-xp 00000000 fc:00 4212 /lib/i386-linux-gnu/libc-2.19.so b776b000-b776c000 ---p 001a9000 fc:00 4212 /lib/i386-linux-gnu/libc-2.19.so b776c000-b776e000 r--p 001a9000 fc:00 4212 /lib/i386-linux-gnu/libc-2.19.so b776e000-b776f000 rw-p 001ab000 fc:00 4212 /lib/i386-linux-gnu/libc-2.19.so b776f000-b7772000 rw-p 00000000 00:00 0 b7779000-b777b000 rw-p 00000000 00:00 0 b777b000-b777c000 r-xp 00000000 00:00 0 [vdso] b777c000-b779c000 r-xp 00000000 fc:00 5916 /lib/i386-linux-gnu/ld-2.19.so b779c000-b779d000 r--p 0001f000 fc:00 5916 /lib/i386-linux-gnu/ld-2.19.so b779d000-b779e000 rw-p 00020000 fc:00 5916 /lib/i386-linux-gnu/ld-2.19.so bfb16000-bfb37000 rw-p 00000000 00:00 0 [stack]

The first column gives the range of mapped addresses, the second column shows the permissions, and the final column shows the path of the file that's mapped there. (See the proc man page for more details.) Notice that the process's address space is laid out with the stack at the top, some libraries below that, then the heap and finally the binary itself.

When v8 is allocating memory, it performs a mmap for (up to) 1 MB at a randomized address. See the OS::GetRandomMmapAddr() function for details. Essentially, it tries to allocate memory in the range 0x20000000 to 0x60000000.

Let's take a look at what that looks like. The target binary has another command line flag -m which will print out the processes address space just prior to jumping to the address specified by the exploit function.

Let's take a look at that by running target -m a.js where a.js contains just the exploit function.

user@sandbox:~/project3$ cat a.js exploit(0); user@sandbox:~/project3$ ./target -m a.js maps: 08048000-09334000 r-xp 00000000 fc:00 192204 /home/user/project3/target 09334000-09335000 r--p 012eb000 fc:00 192204 /home/user/project3/target 09335000-09338000 rw-p 012ec000 fc:00 192204 /home/user/project3/target 09338000-0933e000 rw-p 00000000 00:00 0 0a271000-0a2c5000 rw-p 00000000 00:00 0 [heap] 23600000-23619000 rw-p 00000000 00:00 0 2bc4c000-2bc4d000 r-xp 00000000 00:00 0 36c00000-36c09000 rw-p 00000000 00:00 0 36c09000-36c0a000 ---p 00000000 00:00 0 36c0a000-36c0b000 rwxp 00000000 00:00 0 36c0b000-36c34000 ---p 00000000 00:00 0 3a400000-3a500000 rw-p 00000000 00:00 0 3afa6000-3afa7000 rw-p 00000000 00:00 0 3afa7000-3b0a6000 ---p 00000000 00:00 0 40500000-40509000 rw-p 00000000 00:00 0 40509000-4050a000 ---p 00000000 00:00 0 4050a000-40582000 rwxp 00000000 00:00 0 40582000-40583000 ---p 00000000 00:00 0 47b9f000-47ba0000 r-xp 00000000 00:00 0 4a700000-4a789000 rw-p 00000000 00:00 0 53d00000-53d09000 rw-p 00000000 00:00 0 53d09000-53d0a000 ---p 00000000 00:00 0 53d0a000-53d0b000 rwxp 00000000 00:00 0 53d0b000-53d34000 ---p 00000000 00:00 0 55849000-55860000 ---p 00000000 00:00 0 55860000-55870000 rw-p 00000000 00:00 0 55870000-55879000 ---p 00000000 00:00 0 59a00000-59a11000 rw-p 00000000 00:00 0 5a100000-5a119000 rw-p 00000000 00:00 0 5a300000-5a309000 rw-p 00000000 00:00 0 5a309000-5a30a000 ---p 00000000 00:00 0 5a30a000-5a30b000 rwxp 00000000 00:00 0 5a30b000-5a334000 ---p 00000000 00:00 0 5e000000-5e100000 rw-p 00000000 00:00 0 5e100000-5f000000 ---p 00000000 00:00 0 b6b00000-b6b39000 rw-p 00000000 00:00 0 b6bec000-b6bed000 ---p 00000000 00:00 0 b6bed000-b73f0000 rw-p 00000000 00:00 0 [stack:30331] b73f0000-b7599000 r-xp 00000000 fc:00 4212 /lib/i386-linux-gnu/libc-2.19.so b7599000-b759a000 ---p 001a9000 fc:00 4212 /lib/i386-linux-gnu/libc-2.19.so b759a000-b759c000 r--p 001a9000 fc:00 4212 /lib/i386-linux-gnu/libc-2.19.so b759c000-b759d000 rw-p 001ab000 fc:00 4212 /lib/i386-linux-gnu/libc-2.19.so b759d000-b75a0000 rw-p 00000000 00:00 0 b75a0000-b75b8000 r-xp 00000000 fc:00 5885 /lib/i386-linux-gnu/libpthread-2.19.so b75b8000-b75b9000 r--p 00017000 fc:00 5885 /lib/i386-linux-gnu/libpthread-2.19.so b75b9000-b75ba000 rw-p 00018000 fc:00 5885 /lib/i386-linux-gnu/libpthread-2.19.so b75ba000-b75bc000 rw-p 00000000 00:00 0 b75bc000-b75d8000 r-xp 00000000 fc:00 837 /lib/i386-linux-gnu/libgcc_s.so.1 b75d8000-b75d9000 rw-p 0001b000 fc:00 837 /lib/i386-linux-gnu/libgcc_s.so.1 b75d9000-b761d000 r-xp 00000000 fc:00 2585 /lib/i386-linux-gnu/libm-2.19.so b761d000-b761e000 r--p 00043000 fc:00 2585 /lib/i386-linux-gnu/libm-2.19.so b761e000-b761f000 rw-p 00044000 fc:00 2585 /lib/i386-linux-gnu/libm-2.19.so b761f000-b7620000 rw-p 00000000 00:00 0 b7620000-b76fc000 r-xp 00000000 fc:00 1948 /usr/lib/i386-linux-gnu/libstdc++.so.6.0.19 b76fc000-b76fd000 ---p 000dc000 fc:00 1948 /usr/lib/i386-linux-gnu/libstdc++.so.6.0.19 b76fd000-b7701000 r--p 000dc000 fc:00 1948 /usr/lib/i386-linux-gnu/libstdc++.so.6.0.19 b7701000-b7702000 rw-p 000e0000 fc:00 1948 /usr/lib/i386-linux-gnu/libstdc++.so.6.0.19 b7702000-b7709000 rw-p 00000000 00:00 0 b7709000-b7710000 r-xp 00000000 fc:00 2030 /lib/i386-linux-gnu/librt-2.19.so b7710000-b7711000 r--p 00006000 fc:00 2030 /lib/i386-linux-gnu/librt-2.19.so b7711000-b7712000 rw-p 00007000 fc:00 2030 /lib/i386-linux-gnu/librt-2.19.so b7718000-b771b000 rw-p 00000000 00:00 0 b771b000-b771c000 r-xp 00000000 00:00 0 [vdso] b771c000-b773c000 r-xp 00000000 fc:00 5916 /lib/i386-linux-gnu/ld-2.19.so b773c000-b773d000 r--p 0001f000 fc:00 5916 /lib/i386-linux-gnu/ld-2.19.so b773d000-b773e000 rw-p 00020000 fc:00 5916 /lib/i386-linux-gnu/ld-2.19.so bfca4000-bfcc5000 rw-p 00000000 00:00 0 [stack] Segmentation fault (core dumped)

There's a lot to see there and it's easy to miss what's important. Notice that a lot of the heap memory actually comes in 1 MB-aligned chunks. E.g.,

3a400000-3a500000 rw-p 00000000 00:00 0

Even more interesting is the executables. Every piece of JITted code comes in a chunk that looks like this.

36c00000-36c09000 rw-p 00000000 00:00 0 36c09000-36c0a000 ---p 00000000 00:00 0 36c0a000-36c0b000 rwxp 00000000 00:00 0 36c0b000-36c34000 ---p 00000000 00:00 0

It starts with 0x9000 bytes of nonexecutable data, one guard page — which cannot be read, written, nor executed — the actual executable code, and a final guard page.

You're going to be writing a whole lot of data so it's going to look more like this.

b6b00000-b6b09000 rw-p 00000000 00:00 0 b6b09000-b6b0a000 ---p 00000000 00:00 0 b6b0a000-b6bff000 rwxp 00000000 00:00 0 b6bff000-b6c00000 ---p 00000000 00:00 0

So what happens if the kernel is not able to allocate space at the requested location? Well, the complete answer lies in the source, but from some experimentation with allocating a whole lot of memory (go on, play around with target and try to allocate a bunch of memory, either string data or by JITting a bunch of code over and over), it appears that mmap will first try to allocate in the heap area (roughly 0x20000000–0xb0000000) and if that fails, it will try to allocate between the libraries and the stack or before the start of the binary. This is important for making your attack robust.

What you want to do is fill up a large portion of the heap with data that is fast to produce and then then perform the JIT spray. If you do this, one thing that that seems fairly consistent is that either the 1 MB just after the libraries (or the one after that) will contain the executable code. For example one run of target on my sploit.js placed the executable code at 0xb790a000.

b77a8000-b77a9000 rw-p 00020000 fc:00 5916 /lib/i386-linux-gnu/ld-2.19.so b7800000-b7909000 rw-p 00000000 00:00 0 b7909000-b790a000 ---p 00000000 00:00 0 b790a000-b79ff000 rwxp 00000000 00:00 0 b79ff000-b7a00000 ---p 00000000 00:00 0

A second placed the executable code at 0xb780a000.

b775a000-b775b000 rw-p 00020000 fc:00 5916 /lib/i386-linux-gnu/ld-2.19.so b7800000-b7809000 rw-p 00000000 00:00 0 b7809000-b780a000 ---p 00000000 00:00 0 b780a000-b78ff000 rwxp 00000000 00:00 0 b78ff000-b7900000 ---p 00000000 00:00 0

Depending on how your sploit.js is written, you may find one is more common than the other. It's possible that your code will be in a slightly different location.

Hints

My code uses two files:

sploit.jsandhelper.js.sploit.jscreates 2000 copies of a long string to fill up most of the heap and then it makes 1000 copies of the code inhelper.jsusingloadin a loop.helper.jscontains about 4000 XORs which was right around the limit before it started JITting in a different way.Creating a long string can be sort of tricky. Some JavaScript engines do not do string concatenation in a normal way. Instead, they use a data structure called a rope. One thing that I found worked well was to use string functions like

toLowerCaseandtoUpperCaseto force it to allocate new strings. Something like:s = 'Z’;s = s.toLowerCase() + s.toUpperCase();Make use of both

-pand-m. They're pretty helpful.Here's a handy loop to run try out your exploit.

user@sandbox:~/project3$ while ! time ./target sploit.js; do :; done Segmentation fault (core dumped) real 0m39.406s user 0m33.968s sys 0m5.052s $ echo 'Success on the second run!' Success on the second run! $ exit real 2m22.711s user 0m33.956s sys 0m5.252s

(The long time for the second run was because I was typing these notes and didn't notice that it had succeeded on the second attempt. On my machine, it takes about 40 seconds per run.)